Astronomers have been looking for exoplanets orbiting Barnard’s Star, the nearest solitary star to Earth at just 5.96 light-years away, since its discovery in 1916.

Unconvincing signs of planets in the lonely star’s orbit have been reported previously, but the search efforts have now finally paid off.

Following the announced discovery of a single candidate world in October of last year, a team led by Ritvik Basant of the University of Chicago has confirmed its presence along with another three – bringing the total number of known worlds around Barnard’s star to four.

What makes the achievement even more spectacular is that all four exoplanets in the system are smaller than Earth, the hardest exoplanets to find amongst the wild variety identified in the Milky Way.

“It’s a really exciting find – Barnard’s Star is our cosmic neighbor, and yet we know so little about it,” Basant says. “It’s signaling a breakthrough with the precision of these new instruments from previous generations.”

Barnard’s Star, also known as GJ 699, is an object of interest to exoplanet hunters for several reasons. The first is its proximity: the only stars closer to Earth are the Centauri trinary system.

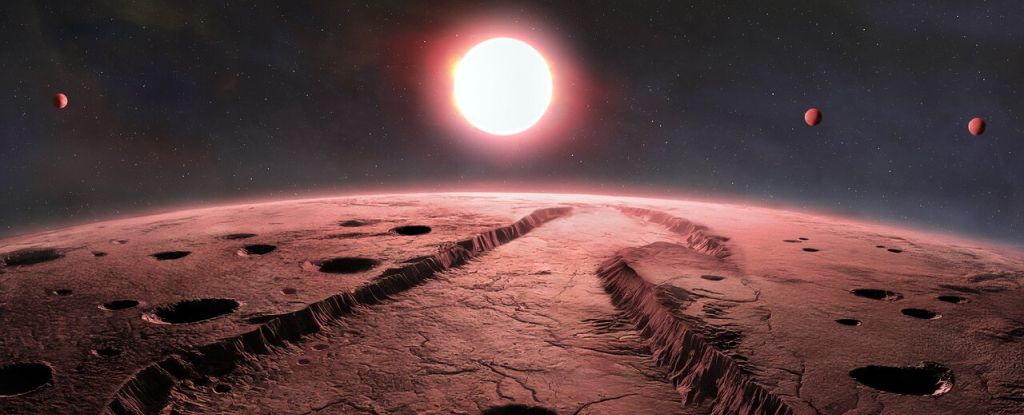

In addition, Barnard’s Star isn’t just a lone star like the Sun; it’s a red dwarf, the most common type of star in the galaxy. Studying it can tell us a lot about our galactic neighborhood and the planets there, planetary systems around single stars, and planetary systems around red dwarfs, such as how habitable they might be.

You might not think so looking at the current catalog of confirmed exoplanets, with nearly 6,000 entries at time of writing, but worlds orbiting alien stars are not easy to spot. Because exoplanets are so much smaller and dimmer than the stars they orbit, astronomers rely on detecting the effects the exoplanets have on their stars.

The two main effects are either a periodic, faint dimming of light as the planet passes between us and the star, or the slight motion, known as radial velocity, as the star moves around the mutual center of gravity of its shared orbit with the exoplanet.

In the case of Barnard’s star, there is no dimming consistent with orbital transits. The detection last year was based on radial velocity, suggesting that the exoplanetary orbital plane is oriented away from our line of sight.

Such signals are very small and difficult to discern. Basant and his colleagues used the MAROON-X planet-hunting instrument mounted on the Gemini North telescope in Hawai’i’ to take observations of the star over 112 nights spread over a three-year timespan. Then, they pored over the data, looking for faint wobbles in the star’s position.

Their results showed the presence of four exoplanets, and allowed the team to calculate the masses and orbital periods thereof.

-

Barnard b has a mass 0.3 times that of Earth, and an orbital period of 3.2 days.

-

Barnard c has a mass 0.34 times that of Earth, and an orbital period of 4.1 days.

-

Barnard d has a mass 0.26 times that of Earth, and an orbital period of 2.3 days.

-

Barnard e has a mass 0.19 times that of Earth, and an orbital period of 6.7 days.

Those orbital periods are all too close to the star to be habitable; at that proximity, temperatures would be too hot for liquid water to be present on the surface. We also don’t know the nature of the exoplanets. At those masses, a rocky composition similar to Mercury is probably the most likely, but tiny gas worlds can’t be entirely ruled out.

The research also reveals how easy it is to miss small exoplanets, even when they’re right under our noses. We haven’t found a lot of Earth-like worlds out there in the galaxy. The Barnard system confirms that this lack is likely the result of our inability to find them.

At just 0.19 times the mass of Earth, however, Barnard e represents the lowest mass exoplanet yet discovered using radial velocity. If those exoplanets are out there, our ability to find them grows stronger and stronger all the time.

“A lot of what we do can be incremental, and it’s sometimes hard to see the bigger picture,” Basant says. “But we found something that humanity will hopefully know forever. That sense of discovery is incredible.”

The team’s findings have been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.